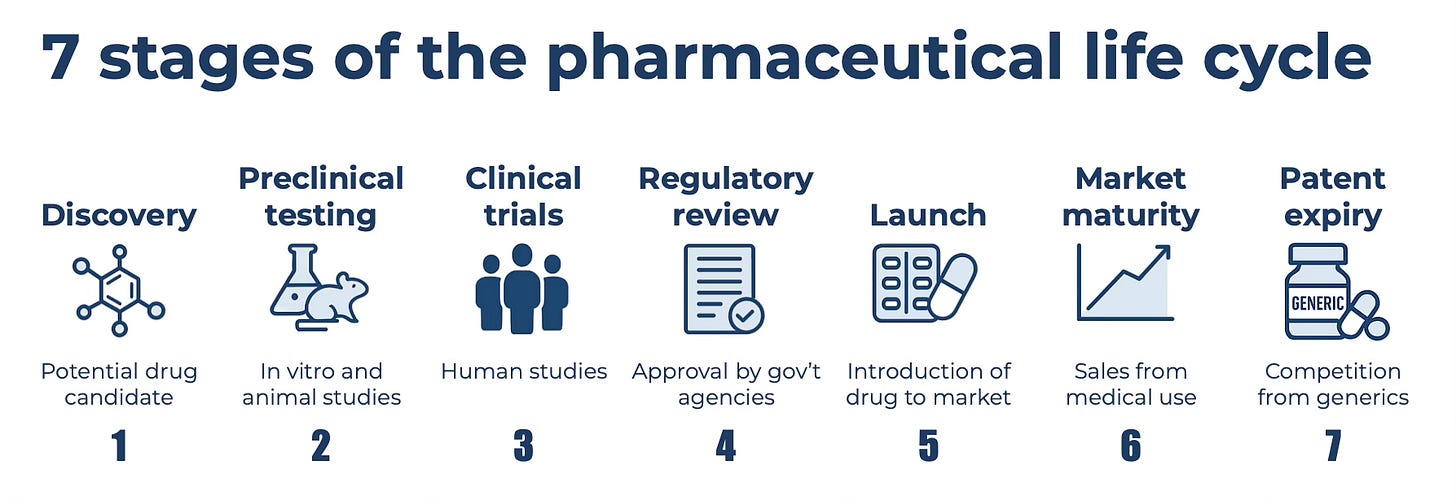

From molecule to market: Overview of the Pharmaceutical Life Cycle

How to read between the lines of drug pipelines, FDA decisions, and market cycles

Why the Pharmaceutical Life Cycle Matters (for Investors)

Every pill in your medicine cabinet represents a decade of science and billions of dollars coupled with a high-stakes race against time. For investors, this race decides who profits and whose fortune vanishes. Understanding the pharmaceutical life cycle is the difference between reading a headline and seeing an opportunity before the crowd.

Use this article as a starting point for your investing journey in the life sciences sector. A large part of understanding a new sector is learning its vocabulary so pay close attention to the words used here and look up any that are unfamiliar, as you will continually encounter them during investment research.

1. Discovery: Identifying a potential drug candidate

Value investors are unlikely to find deals this early in the life cycle.

It all starts here. A scientist identifies a biological target (like tumor necrosis factor, or TNF) key to a disease-related pathway (cancer and inflammation pathways in TNF’s case) and researchers test a large array of compounds with the hopes of identifying some that interact with it. Fun fact: blockbuster drugs (>$1 billion annual revenue) like Remicade and Humira interact with TNF and started on this discovery step in the 1990s.

Why this matters to investors

It seldom matters to individual retail investors. Of the thousands (or tens of thousands) of compounds that enter this stage, very few make it to market.

2. Preclinical testing: From the bench to living systems

Assets undergoing preclinical testing are too early for consideration from retail investors.

Once a compound is known to interact with the biological target of interest, it needs to be tested in humans to ensure it works as needed, to assess the dosages at which it works as effective treatment, and to review adverse effects that may result from treatment. But before a compound can reach a human, it must pass 2 types of preclinical studies: (1) in vitro studies in a laboratory (think of a stereotypical chemistry lab with glass beakers) and (2) studies in animals, often mice or rats.

This critical stage minimizes risk as much as possible before a compound ever reaches a human. If a compound successfully passes this stage and is a candidate for clinical trials, an application for an investigational new drug (IND) can be submitted.

Why this matters to investors

Like the discovery stage, preclinical testing is too early for most retail investors. Less than 100 drugs launch in the United States annually, while thousands of IND applications are filed. The odds are brutal.

3. Clinical trials: Safety and efficacy in humans

The market often relies on subjective assessments to determine asset value. This often results in mispricing, providing you an opportunity to invest.

Clinical trials are where science and uncertainty meet market psychology, with human testing being the most critical and costly step for drug approval. You should be familiar with phases 1-4 of clinical trials, but your focus should primarily be on phases 2 and 3.

After the phase 1 trial establishes safety and dosage ranges in humans, a phase 2 trial is initiated as a pilot to test whether the drug is effective and to assess its adverse effect profile. Promising candidates then proceed to large-scale validation in a phase 3 trial that confirms positive results observed in the phase 2 trial and compares the drug candidate to either a placebo or the existing standard of care. If successful, the drug could proceed to regulatory review and launch.

Post-launch, a phase 4 clinical trial could be launched as post-marketing surveillance to evaluate how the drug works in the long-term. Also, keep in mind that the clinical trial process is not always as clear-cut as outlined above. For example, phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials can be combined into a phase 1/2 trial that could accelerate the development process.

Why this matters to investors

Phases 2 and 3 lie at the heart of valuation and are where market mispricing often begins. Consider Viking Therapeutics’s announcement of positive phase 2 trial results near the end of February 2024 and the consequent >2x of its stock price from less than $40 to over $80 a share.

4. Regulatory review: FDA decision moment

Regulatory responses can provide bargain situations for the keen investor.

Upon the successful completion of clinical trials (step 3), pharmaceutical companies submit either a new drug application (NDA) for small molecule assets or a therapeutic biologics application (BLA for biologics license application) for biologic assets. These documents can be thousands of pages long and contain detailed trial data, some of which may not be publicly available. The FDA uses them to either approve a medication (green light to launch), return a complete response letter (more data required), or reject a medication (no launch in the United States). Of note, there are other applications companies can use, such as the abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) or the over-the-counter drugs application (OTC), but these form the minority of new launches.

Why this matters to investors

The regulatory review step is a significant source of uncertainty; again, not a source of quantifiable risk but a source of unquantifiable uncertainty. Sometimes, despite a successful phase 3 trial, companies may receive a response letter, delaying or derailing expected earnings. Although unexpected non-approvals are not very common, you must account for these by building in a margin of safety to your valuations.

When building a discounted cash flow model to value an asset, it would be a mistake to assume that cash flows begin at the end of a successful clinical trial. The commercial launch of a pharmaceutical asset follows many months after conclusion of a phase 3 trial due to trial calculations / publication, regulatory submission, review period, and commercial launch planning.

Importantly, regulatory responses can provide bargain situations for the keen investor since markets often overreact to regulatory updates. As an example, a drug with high expectations receiving a response letter (not approval, not rejection) may cause a downward market overreaction in the pharmaceutical company’s stock. If you read the response letter and recognize that the drug is likely to be approved (albeit with a delay) or if you see that the company’s expected cash flows from other assets in its portfolio justify a higher valuation, you could potentially buy the company’s stock at a bargain price.

5. Launch: Make or break moment

A brilliant drug can fail commercially and a subpar drug can exceed earnings expectations.

FDA approval is just the beginning. A commercially successful drug still needs to win over patients, doctors, and insurers. As part of their launch plan and commercial strategy, pharmaceutical companies need to build and mobilize a sales force, invest significant capital in marketing, negotiate payer coverage, and setup post-market activities for adverse effect monitoring or potential indication expansion. Successful drug launches require pharmaceutical companies to navigate an increasingly complex healthcare system and are critical to value creation.

Why this matters to investors

Like regulatory review, commercial launches carry uncertainty, but with more levers for analysis. Physician adoption, payer coverage, and the company’s launch history can all shape commercial outcomes.

You need to remember that, for better or worse, how good a drug is does not always correspond to its commercial success. A brilliant drug can fail commercially and a subpar drug can exceed earnings expectations. Consider the example of Aduhelm that gained approval but faced commercial challenges and did not become a blockbuster drug.

6. Market maturity: From the balance sheet to the income statement

Prior to [patent expiry], the company enjoys a monopoly for selling a compound in the United States.

These are the golden years of profitability when years of upfront capital investment turn into high-margin profits. To extend success, company’s often pull levers like label expansion and alternative formulation development. Until patent expiry, the company enjoys a monopoly for selling a compound in the United States. Following patent expiry, other companies can manufacture the same compound and compete.

Why this matters to investors

This (along with step 3) should be an area of focus for you since it is the primary revenue driver in the life cycle. It is challenging to accurately model the number of patients who could benefit from a medication and the price at which a medication would sell. But coming close, particularly for medications that achieve blockbuster status (>$1 billion annual revenue), can be immensely rewarding for investor portfolios.

7. Patent expiry: Understanding the cliff

Pharmaceutical companies do have strategies at their disposal to minimize the decrease in revenue, and other players in the healthcare system have their own strategies to counter these.

Also known as loss of exclusivity, patent expiry opens the door for generic or biosimilar competitors that cause market share losses and share price declines. However, pharmaceutical companies do have strategies at their disposal to minimize the decrease in revenue, and other players in the healthcare system have their own strategies to counter these. This complicates the prediction of expected cash flows.

Why this matters to investors

Unless you specialize in drug pricing, you do not need to model this in detail. Assume post-expiry cash flows decline sharply and focus on whether the company has a healthy R&D pipeline with the next wave of drugs. Post-patent expiry cash flows are years or decades in the future and small changes in assumptions will not meaningfully affect net present value.

Concluding thoughts: Long-term rhythm of risk and reward

The pharmaceutical life cycle involves early optimism, mid-stage testing, late-stage reward, and unavoidable decline. Don’t fear this rhythm, time it. Smart investors do not invest in headlines. The best returns often come not from predicting the next miracle drug, but from understanding how well a company manages this cycle.

No content shared in this article constitutes financial advice; see disclaimer for details.